American whiskey is the by-product of years of European migration into the Americas, rebel ingenuity, and our ugly “Manifest Destiny” era. The winding story of the nation’s favorite spirit has a place amongst the big moments in the very history of this nation. Rye whiskey and Bourbon were created out of a necessity of place and time. Eventually, they became the backbone of the Federal government’s western expansion, and helped fuel a movement that would lead to Prohibition.

HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

During British colonial expansion, rum was king. Plantations in the Caribean processed sugar cane into molasses. In turn, that molasses made its way to the American colonies along the Atlantic coast where early British-American distilleries processed it into rum. Rum was so popular that Rhode Island alone was receiving 1,000,000 gallons of molasses from El Carib yearly by 1770.

There was another spirit starting to make a mark at this time, largely thanks to a Scottish preacher in Virginia. Even in these early days, there was a large contingent of European migrants fighting the evils of alcohol via Puritanical laws. The proponents of spirits recruited Elijah Craig to be their champion and maintain the ancient link between church and spirits in the New World.

Craig ran his own stills in Fayette County, Virginia at the time, and is often credited with the invention of bourbon whiskey. Let’s not fool ourselves here. There were undoubtedly other stills behind plenty of farms and churches that were likely also distilling grain spirits, but given Craig’s involvement in popularizing American style whiskeys with corn and rye as primary ingredients in the mash bill, he tends to get the bulk of the credit for ‘inventing’ the style. As with all of American history, the myth always trumps the fact.

Craig’s distillery in Georgetown, Virginia (now located at Heaven Hills in Kentucky), did have one big advantage: He was — again, allegedly — the first to age his whiskey in new charred American oak casks which is what makes bourbon bourbon. Ironically, Bourbon County, Kentucky, has little to nothing to do with the invention of bourbon. Basically, bourbon was made in the western reaches of the American colonies with a distinct corn-fueled mash bill. At the same time, rye mash was being used to make the very popular rye whiskey in the eastern reaches of the American colonies and Canada. Craig’s slave-labor-fuelled lands would eventually become Kentucky in 1792. But if we’re using Craig’s distillery as the inception of the bourbon … well, that means it was invented in Virginia technically. All of that being said, by the time the American Revolution rolled around American style whiskey was being distilled all over the American colonies in one respect or another, mostly in unofficial home stills.

FUNDING MANIFEST DESTINY

George Washington was a huge drinker. His bar tabs during the American Revolution are the bar bills of legend. President Washington was also obsessed with westward expansion and the eradication of the American Indian. So… don’t go wishing you could have a drink with him just yet.

General Washington proved his prowess at genocidal mania during the American Revolution — which was just as much about throwing off the yoke of British imperial rule as it was about the destruction of Native America and expanding west. The vilest campaign among many was the Sullivan Expedition. Washington ordered a scorched-earth strategy that sent waves of refugees fleeing into Canada after over 40 towns and cities were burned to the ground. After that war was won, President Washington and the new American elite looked further west to expand their new nation. To fund the westward expeditions and the so-called Indian Wars, Washington needed a lot of money. It costs cash to manifest a destiny.

To fill his war chest, President Washington turned to something he knew all too well — whiskey. Washington tread on American distillers by levying a huge tax on whiskey stills and requiring all stills be licensed under federal law. By 1794 this act was so hated that there was an actual rebellion in Pennsylvania. A year later Elijah Craig would be arrested for refusing to pay taxes on his now “illegal” stills.

The government cracked down hard and sent much of the industry underground. Intrepid whiskey distillers created a new way to transport their tipple without detection of the American government. They’d hide small glass flasks in their boots to smuggle whiskey over county and state lines. Thus the notion of “bootleggers” was born.

Then things started to get out of hand. Battles were pitched between whiskey rebels fighting off government troops with machetes and pitchforks while bagpipes wailed away over the battlefields. Distilleries were burned to the ground. Chaos reigned. President Washington marched an army of 12,950 soldiers to face the 7,000 whiskey rebels in Pennsylvania. Amazingly, the rebellion was put down with little fighting and only a few casualties. An agreement was met in the face of grave federal consequence to resisting the new federal law. Tax revenue from whiskey started flowing to the U.S. Treasury and men and guns started flowing west. Suddenly, whiskey was a foundational part of America.

Taxed American Whiskey flourished for just over 100 years. Then the Temperance Movement unleashed some unintended consequences we’re still dealing with today. Banning spirits from society, especially an American one, turned out to be a disaster of epic proportions. The early feminist movement was instrumental in shifting public opinions — often with flat out lies about alcohol and the ills it rained on society. These philosophies aligned with the early Puritanical leanings of earlier European Americans.

The Temperance movement was most successful in getting alcohol banned nationwide. This led to an unprecedented rise in organized crime, untold loss of life, and a system that would later also ban cannabis, cocaine, and heroin from public use, (thereby creating the same vile organized crime rackets around those products as well).

The effect of prohibition was deep. Not only did it kill distilleries, it also nearly killed cocktail culture in the country. During the dark years of prohibition, getting drunk was all about expediency. So waiting for bartenders to mix a base with a bitters and sweetener went out the window. The quality and quantity of American whiskey were so damaged that it’s only today that we are fully recovering from its ill effects — nearly 100 years later.

THE BIRTH OF THE STYLE

As the 18th century turned into the 19th century, many of the standard practices and brands we’ve come to know and love came to life — in large part thanks to government regulation of the industry and taxation. For example, a German migrant named Jakob Böhm was granted a distilling license in 1795 as the Whiskey Rebellion was winding down. Jim Beam is still distilled by the descendants of Jakob Böhm to this day.

Bourbon tends to be a sour mash. That’s when the remanents of the previous mash are used to start the next mash during the fermentation process. Think of it like a sourdough starter that carries the lineage of the mash bill from generation to generation of distillations.

Bourbon and rye are barreled for minimum two years and maximum six years. Generally, almost all of them are barreled for four years on average. For bourbon, the barrels are only used once and then they’re shipped to Ireland and Scotland to be used again and again. Since Irish and Scottish whisk(e)y have a much longer barreling time (sometimes decades) the real cost comes in housing thousands of barrels for years on end — meaning bourbon and rye can keep their prices relatively low comparatively.

A Straight Whiskey is a spirit that hasn’t been blended with any other grain spirits, additives, or colors. It cannot exceed 80 percent (160 proof) of alcohol. So a ‘Straight Rye Whiskey’ means that you’re drinking a whiskey made solely with rye. Whereas a ‘Straight Whiskey’ has to have at least 51 percent of a single grain spirit. This also dovetails with the label ‘Bottled In Bond.’ This designates a single class of spirit that’s bottled in a bonded warehouse (government approved place for taxable goods) and has a no more than 50 percent (100 proof) alcohol. This means that theoretically you can buy a bottle of ‘Kentucky Straight Bourbon Bottled In Bond’ and it just means you’re drinking a classic bourbon mash bill that’s generally un-altered with additives and bottled in a government approved setting.

You’ll find plenty of variation from the usual two to six years of aging for the average American whiskey. Corn whiskey generally tends to be unaged. Sometimes it’s simply filtered through oak, which allows it to be designated a whiskey instead of a moonshine. Wheat, malted rye, and malted barely make appearances across the broad range of American whiskeys, depending on where you are and who’s distilling. Basically, each type of whiskey has to contain 51 percent of the labeled ingredient. So if it says a Rye, that means it has to have at least 51 percent rye distillate. If it says bourbon, it has to have at least 51 percent corn distillate. The only exception is Corn whiskey which has to have 80 percent corn distillate.

TEN BOTTLES TO GET YOU STARTED

So what’s the best American whiskey out there? We’ve put together a short list of some of our favorites to help you build a collection.

MICHTER’S ORIGINAL US*1 UNBLENDED AMERICAN WHISKEY

Michter’s makes solid whiskey across the board. You won’t be disappointed in sampling any of their bottles. However, we’ve chosen their US*1 Unblended American Whiskey because it’s a great introduction to American Whiskey in general.

The unblended whiskey means that there are no neutral grain spirits used to cut the distillate during aging. The whiskey cannot be called a bourbon since it’s aged in old bourbon barrels and new charred oak. This imparts a distinct spice, vanilla, caramel, and dried apricot taste to this whiskey that’s just delightful. Its edges are soft and refined making this one go down very easily.

BULLEIT BOURBON 10 YEAR OLD

This Frontier Whiskey is a classic among whiskey aficionados. Bulleit’s 10 Year Old Straight Bourbon did not disappoint whiskey lovers when it was released.

This bourbon whiskey is the same mash bill as Bulleit’s insanely popular standard bourbon. The only difference is the aging. This one spent 10 years mellowing in new charred American oak barrels. That aging lends a distinct oakiness, vanilla, and dried fruit taste that almost starts to get a smokiness to it. It’s an interesting take on aged bourbon that works perfectly on the rocks or in a Manhattan.

WHISTLEPIG FARMSTOCK

WhistlePig made waves in the industry when they released their Canadian Rye onto the market. Now, finally, they’ve created their own Rye from their farm in Vermont. WhistlePig Farmstock is a stellar American Rye that deserves a spot on every whiskey lover’s shelf.

This gorgeous Rye contains 20% WhistlePig’s ‘triple-terroir’ whiskey aged in Vermont oak for at least 1 year, 49% 5-year rye whisky from Alberta Distillers also aged in Vermont oak, and 31% 12-year rye from MGP in Indiana. Expect good hits of orange rind, cracked peppercorns, cinnamon, and creamy vanilla, which softens the edges of the rye — making one of the smoothest whiskeys on the market.

NELSON’S FIRST 108 TENNESSEE WHISKEY

Nelson’s GreenBrier was one of the distilleries destroyed by Prohibition. It was resurrected recently by descendants of the distillers and they’ve just released their first line of in-house made whiskeys. Nelson’s First 108 is a throwback to the great whiskeys of a bygone era that embraces the modernity of today’s palate.

This Tennessee Whiskey was aged for four years. Expect a rush of caramel, vanilla, oak, and a hint of black tea and toffee. This is a very limited release, so you’ll have to get yourself to Nashville to pick up a bottle. But the trip is worth it for a whiskey this good.

1792 SMALL BATCH BOURBON

1792 denotes the year Kentucky officially became a state. 1792 Small Batch Bourbon is here because it’s an interesting take on bourbon with about 20 percent of its mash bill containing rye.

The addition of rye distillate and aging of eight years brings out a lot of flavors here. There’s a distinct peppery forward flavor that you often don’t have with bourbons. Expect a maple sweetness, honey, orange rind, vanilla, and a warm, spicy finish. It’s kind of like bourbon plus — or a nice bridge between the spiciness of the rye and the smooth creaminess of a bourbon.

STRANAHAN’S COLORADO WHISKEY

Stranahan’s were the first micro-distillers to work in the Colorado Rockies. They devised a unique pot and column still hybrid to make their whiskey with a 100 percent malted barely — a rarity in American whiskeys.

Although malted barley is used, don’t expect a Scotch here. There’s a slight smokiness on the finish but that’s where the analogs to Scotch end. Expect a distinct orange, cinnamon, and toffee taste with hints of an old library full of musty leather chairs (but, like, in a good way). This is a truly unique American whiskey that’s worth seeking out.

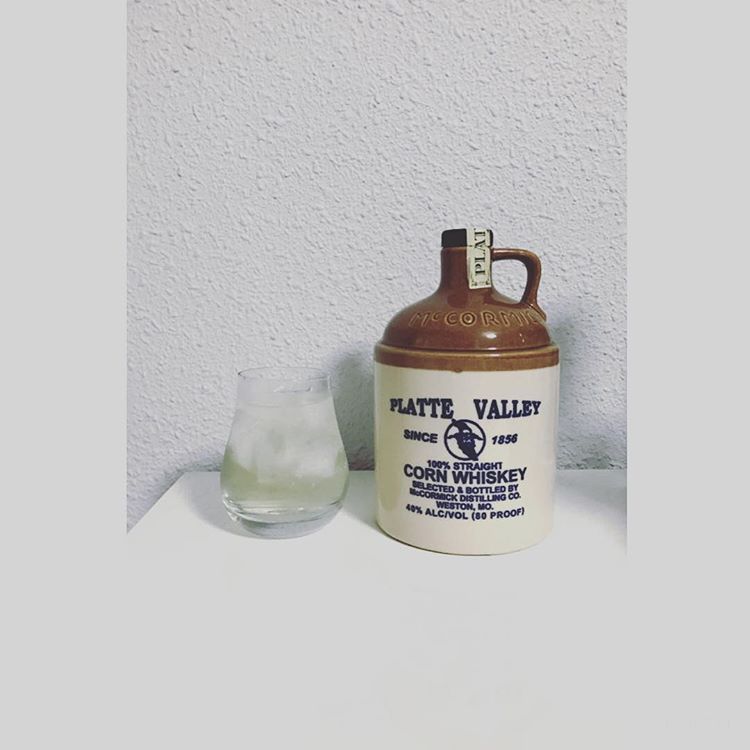

PLATTE VALLEY CORN

Platte Valley Corn Whiskey is distilled in Illinois and bottled in Missouri. This Corn whiskey spends about three years in used barrels — thus it’s not a bourbon. Overall, we’re talking about a whiskey that still retains its moonshine roots with a slight burn.

There’s a sweetness to this whiskey, since it’s 80 percent corn-fueled. That sweetness leans into candy and caramel territories. There’s a definite taste of corn, vanilla, and a hint of spice on the end. Expect to get a very warm feeling from the corn distillate that’ll go straight to your head. This is, after all, closer to what all whiskey was before barrel aging became more and more refined.

WESTLAND AMERICAN SINGLE MALT WHISKEY

Here’s another American Single Malt that’s worth every cent. Westland’s American Single Malt uses local, Washington-grown malted barley in their mash bill. Where this whiskey deviates from Scotch is the barreling. Westland’s Single Malt is barreled in new charred American oak like a bourbon — whereas Scotch is barreled in used bourbon barrels (generally).

The malted barley imparts a distinct roasted quality to the whiskey. Expect strong hits of coffee, toffee, and dark chocolate alongside hints of vanilla, tobacco, and well-worn leather. This is a deeply satisfying American Single Malt that gives loving nods to its Scottish roots while taking the style to new heights.

RUSSELL’S RESERVE SINGLE BARREL RYE

Russell’s Reserve from Wild Turkey is a big whiskey. The 51 percent rye mash bill is aged in deeply charred new American oak. The barrels are hand selected by the Russells to impart the best flavors into the rye.

Expect a heavy hit of baking spices, tobacco, and rye bread. This is a big whiskey and all the flavors shine brightly. The spiciness is strong and counterpoints a slight vanilla and sweet oakiness.

BOOKER’S RYE

Hailing from the Beam Distillery in Clermont, Kentucky comes 2017’s whiskey of the year. Master distiller Booker Noe laid down this whiskey in 2003 — a year before his passing. After 13 years in a sun-soaked warehouse, it has become one of the best whiskeys you can drink.

Expect a heavy hit of baking spices, tobacco, and rye bread. This is a big whiskey and all the flavors shine brightly. The spiciness is strong and counterpoints a slight vanilla and sweet oakiness.

There’s a lot of spice here from clove to nutmeg to cinnamon to cracked peppercorn. There’s also a distinct chocolate and brown sugar edge that ties the rye spice and vanilla oak together nicely. It’s one of the greatest ryes to come out of America this decade. Find one if you can!